For foreign families, the island’s communal warmth sparks a profound—and sometimes tense—negotiation over boundaries, safety, and the meaning of community.

BALI — The voice in the video is firm, edged with protective anxiety. “Don’t touch my baby. Don’t touch hands, don’t touch feet. Don’t touch my baby if I don’t know you.”

It is a plea from a foreign parent, likely from North America or Europe, expressing a boundary considered fundamental in their culture. Yet in Bali, this request often collides with a social reality as constant as the tropical heat: a society where children are warmly embraced as part of the community.

The contrast between Western ideas of children as private family territory and the Balinese belief that children belong to the wider social circle creates one of the island’s most intimate and revealing cultural encounters. It unfolds daily in cafés, local markets, and neighborhood shops—a quiet, ongoing negotiation between personal boundaries and communal belonging that defines one of the island’s most profound cultural exchanges.

The Private Infant vs. The Shared Celebration

For many expatriate and visiting parents, the first reaction can be deeply visceral. In societies where unsolicited interaction with a stranger’s child may be viewed as intrusive, spontaneous gestures such as cheek-pinching, playful conversation, or offers to hold a baby can trigger unease.

This tension becomes particularly sensitive for parents of newborns, premature babies, or children with health vulnerabilities. The recorded testimony of a parent of a NICU graduate reflects this anxiety clearly, repeating the protective message: “If you are a stranger, do not touch my baby.”

Within their cultural framework, such caution is neither exaggerated nor unusual. It reflects a parenting philosophy—often rooted in individualistic child-rearing models—shaped by privacy, safety awareness, and strong nuclear family autonomy.

Discovering a Different Social Rhythm

Yet many foreign parents living in Bali describe a gradual, often surprising, shift in perception. What initially feels overwhelming frequently transforms into admiration and gratitude.

Another parent recounts with delight, “Someone just played with my child outside and even took him behind the bar. I found it beautiful.”

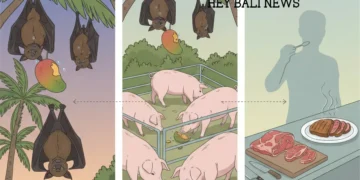

Over time, many begin to recognize that these gestures rarely stem from disregard for boundaries. Instead, they reflect ketulusan — sincerity — and kebersamaan — a deeply rooted sense of togetherness that is foundational to Balinese banjar (community) life. Within this social fabric, the presence of a child is seen as shared happiness and, to some degree, a shared responsibility.

A crying baby, for instance, is rarely treated as a disturbance. Restaurant staff, vendors, or nearby families may instinctively step in to help soothe or entertain the child, allowing parents a brief moment of rest. For many expatriate families, this environment feels unexpectedly supportive and remarkably free of the judgmental scrutiny common in more individualistic societies.

Finding the Cultural Middle Ground

Life for international families in Bali thus becomes a subtle, daily balancing act rather than a complete cultural surrender.

Many parents learn simple Bahasa Indonesia phrases to gently set boundaries, such as explaining that the baby is sleeping or unwell. Simultaneously, they often discover comfort in loosening some of their own caution in safe, familiar environments. Children frequently become part of spontaneous interactions with restaurant staff, shopkeepers, or neighbors, creating social bonds that many families describe as uniquely enriching—a form of informal, village-style integration.

A Living Lesson in Community Parenting

Beyond the personal experience, this ongoing dialogue presents a broader reflection on how societies conceive of childhood and care. For children, exposure to this diverse, affectionate social web can foster confidence, adaptability, and cultural openness.

For parents, the experience can challenge deeply ingrained notions about control, privacy, and self-reliance. It introduces the tangible possibility that parenting can extend beyond the immediate family, supported by a wider, informal circle of care.

The journey from instinctively saying “don’t touch my baby” to appreciating a community’s warmth illustrates one of Bali’s most powerful, if quiet, lessons. In a world where parenting can feel increasingly isolated, the island offers a living alternative—a perspective where childhood unfolds within a broader social embrace, shaped by a quiet but powerful belief: that the village, in its own way, still has a role in raising the child.