By Giostanovlatto

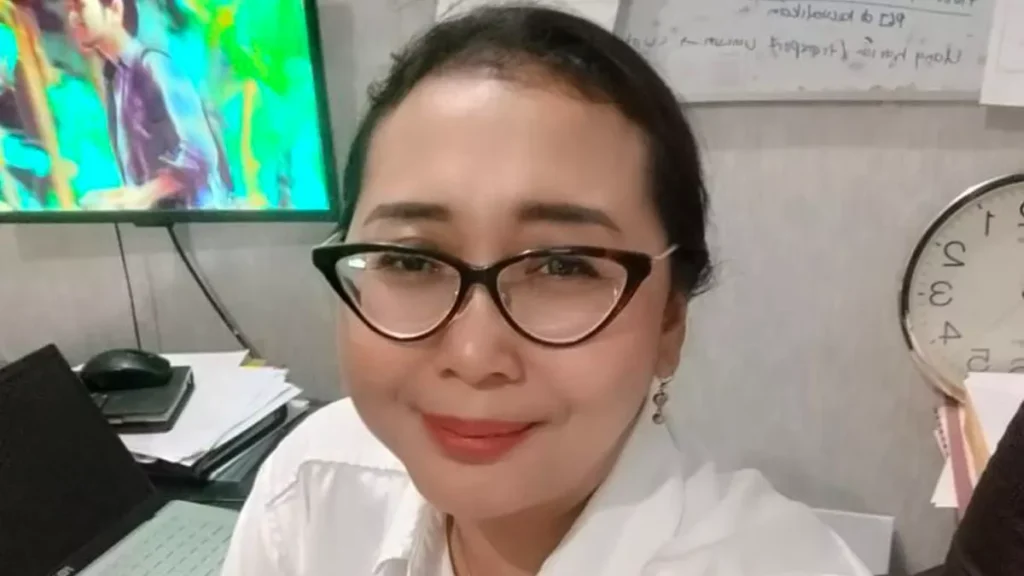

In consultation with Prof. Dr. Werdhi Sutisari, SH., M.H., PhD

Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy, Asean University International

BALI, Indonesia — In the tranquil surroundings of Bali’s Jimbaran immigration detention center, a quiet crisis of legal ambiguity is unfolding. For nearly four months, Andrew Joseph McLean, a New Zealand national, has been held without clear criminal charges, without deportation, and without the procedural clarity that modern rule of law demands. His case has become more than an immigration footnote—it is a litmus test for Indonesia’s reformed penal code and its commitment to justice in an international context.

What began as an alleged assault report in Badung last August has morphed into a confounding legal paradox. Mr. McLean was never formally arrested by police. Instead, immigration authorities detained him for an administrative violation in September. Just as deportation seemed imminent, a police letter in late November requested a postponement, citing ongoing investigations. Since then, he has lingered in a procedural void—not a criminal suspect, not a deportee, but a man indefinitely suspended between decisions.

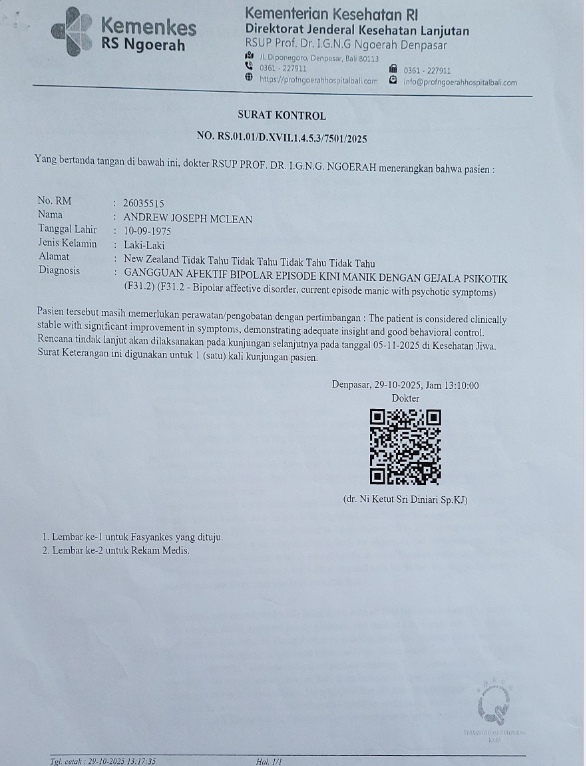

But it is the emergence of Mr. McLean’s documented mental health condition that elevates this from a bureaucratic delay to a profound legal and ethical dilemma. Medical records from Bali’s Sanglah General Hospital diagnose him with Bipolar Affective Disorder, Manic Episode with Psychotic Symptoms. In the hands of a skilled legal scholar, this diagnosis is not merely clinical—it is juridical.

“The law,” explains Prof. Dr. Werdhi Sutisari, a distinguished Indonesian legal philosopher, “is not meant to punish those who cannot comprehend their own actions.”

In a detailed analysis shared with this writer, Prof. Werdhi frames the case through the lens of Indonesia’s new Criminal Code (Law No. 1/2023), a document meant to reflect a more humane, restorative vision of justice. At its heart lies Article 44, which explicitly states that those who commit acts under severe mental incapacity due to illness shall not be criminally punished.

“This is not a loophole,” Prof. Werdhi emphasizes. “It is a fundamental principle. A person with severe mental disorder lacks mens rea—the guilty mind necessary for criminal liability. The new code understands this. It shifts the focus from punishment to protection and rehabilitation.”

Indeed, under the revised code, individuals like Mr. McLean—if proven to have been in a state of psychotic breakdown during the alleged incident—would not face prison. Instead, the court could impose maatregel: measures such as compulsory treatment, medical supervision, or rehabilitation. This approach is consistent with a 2012 Supreme Court ruling (No. 55 K/Pid/2012), which held that persons with severe mental illness should receive care, not incarceration.

Yet here lies the rupture between legal theory and practice. Despite the medical certificate from a state hospital—a document Prof. Werdhi describes as “a strong piece of medical evidence”—Mr. McLean remains detained under immigration authority, while a criminal investigation hangs over him without apparent progress.

“When the state suspects someone of a crime,” Prof. Werdhi notes pointedly, “it must act with clarity and urgency. Detaining a person in a legal gray zone, under one pretext while investigating another, undermines the very rule of law Indonesia seeks to uphold.”

The professor’s concern touches on a core vulnerability in Indonesia’s legal architecture: the coordination—or lack thereof—between immigration enforcement and criminal justice agencies. Mr. McLean’s limbo appears less a deliberate strategy than a systemic inertia, where one institution’s request to “wait” overrides another’s mandate to resolve or release.

For Bali, a island sustained by global tourism and expatriate trust, the implications are tangible. The island sells itself as a place of order and beauty, a seamless blend of culture and modernity. Cases like Mr. McLean’s whisper a different narrative—one of procedural ambiguity, where rights can stall in the space between agencies.

International observers, including foreign consulates and human rights advocates, are watching. The treatment of a foreign national with documented mental health needs tests not only Indonesia’s penal reforms but also its adherence to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which it has ratified.

What happens next?

Prof. Werdhi suggests a clear path forward: the police should immediately seek a forensic psychiatric examination (visum et repertum psychiatricum) to determine Mr. McLean’s mental state at the time of the alleged offense. If he is found to have lacked criminal responsibility, the case should be diverted from the penal track to a therapeutic or administrative one, possibly culminating in supervised care and deportation.

Until then, Andrew McLean waits. And while he waits, so does Bali’s reputation as a destination where justice is not only picturesque but also predictable, fair, and humane.

In the words of Prof. Werdhi: “Law should provide certainty, not suspense. Especially in paradise.”

This opinion analysis is based on written correspondence and interviews with Prof. Dr. Werdhi Sutisari, SH., M.H., PhD, conducted in early 2026.