Long before the neatly drawn nations of today’s map existed, the islands of what is now Indonesia formed the vibrant, strategic core of a sprawling maritime world, a history that reframes our understanding of the region’s interconnected past.

The narrative of Southeast Asia is often told through the lens of its modern nation-states: Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines. Yet, for centuries before these political entities took shape, the region was defined not by borders but by thalassocracies—great sea-based kingdoms whose influence flowed across the water, connecting peoples, cultures, and commerce. At the heart of this ancient network sat the Indonesian archipelago, with its strategic islands serving as the hubs of empires that projected power and culture across the region.

Sriwijaya and Majapahit: The Archipelagic Engines

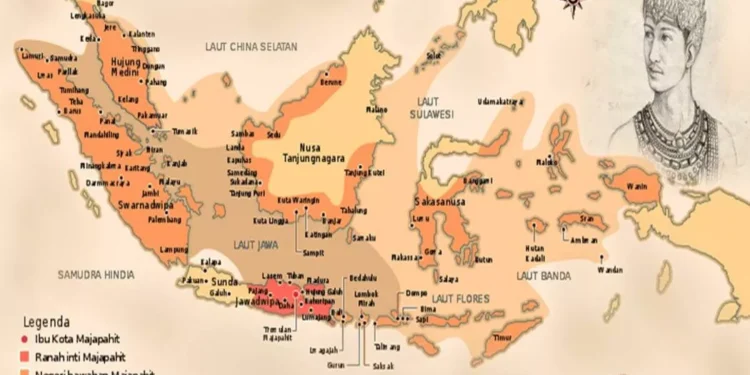

From roughly the 7th to the 14th centuries, the Sumatran-based Srivijaya empire dominated the vital Strait of Malacca, controlling the spice trade and acting as a pivotal centre for Buddhist learning. Its influence extended north to parts of the Malay Peninsula and mainland Southeast Asia. Centuries later, the Javanese Majapahit empire, under the ambitious vision of Prime Minister Gajah Mada, forged a vast “mandala” of influence. While direct control was often exercised over core areas, its political and cultural sphere reached across the archipelago and beyond, touching parts of the Malay Peninsula and the Philippine archipelago.

This was a world where Bali was not a remote island paradise, but an integrated part of a greater Javanese cultural and political sphere, deeply connected to the ebb and flow of archipelagic power.

Reframing the Narrative: Connectivity Over Conquest

To view this history simply through the anachronistic lens of modern national ownership—”countries that were once part of Indonesia”—is to miss its profound essence. The more accurate and compelling framework is one of cultural diffusion, economic networks, and political spheres of influence.

The great archipelagic kingdoms were not nation-states as we understand them today. They were networks. Their “control” was often manifested in trade monopolies, tributary relationships, and cultural patronage rather than direct administration. Ports like Temasek (early Singapore) thrived because they were nodes in these networks, frequented by Srivijayan and later Majapahit traders. The spread of Hinduism, Buddhism, and architectural styles, along with linguistic traces, stand as enduring testaments to this era of connectivity, not conquest.

Bali’s Place in the Ancient Matrix

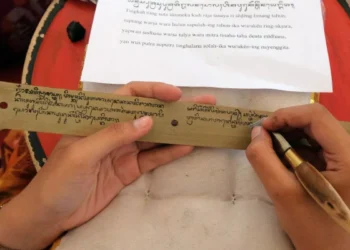

For Bali, this history is foundational. The island’s deep Hindu traditions, its ancient scripts (aksara) preserved on palm-leaf manuscripts (lontar), and its temple architecture all speak to its active participation in these centuries of cross-sea exchange.

Bali was a recipient and a transmitter within this vast web, linked to Java, and through it, to the broader currents of Asian civilization.

For the global reader, expatriate, or traveler in Bali today, this perspective enriches the experience. It moves beyond seeing Bali as merely a beautiful destination and frames it as a historical crossroads—an island whose culture was shaped by, and contributed to, a sophisticated regional system long before passports or border controls existed.

In an era when Bali is once again a nexus of global flows—of tourists, digital nomads, and international capital—its ancient legacy as a strategic and cultural crossroads feels less like distant history and more like a deeply ingrained pattern reasserting itself.

Understanding this shared maritime past allows for a deeper appreciation of the subtle cultural threads that still bind Southeast Asia, reminding us that the region’s true story is one of dynamic connection across the seas.