Written by Giostanovlatto, Founder of Hey Bali and Observer of Tourism & Sustainability

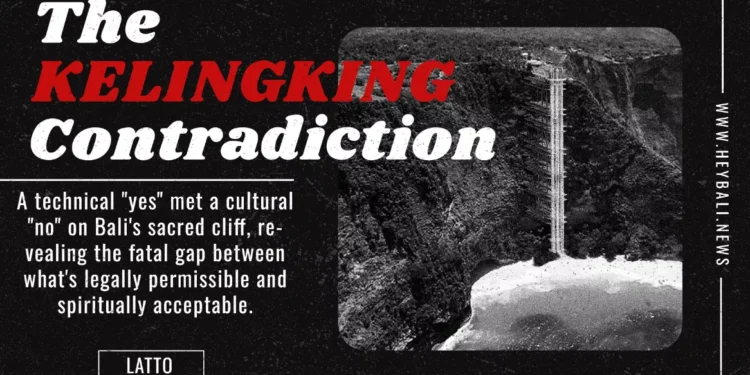

KLUNGKUNG — In the grand theater of Balinese development, a single piece of paper often plays the lead role. Dated January 25, 2023, and signed by the Head of the Bali Public Works and Spatial Planning Office (PUPR), a technical recommendation letter gave formal, bureaucratic life to the most controversial project on the island: a 180-meter glass elevator clinging to the sacred cliff face of Kelingking Beach.

Months later, Governor Wayan Koster—the man popularly known as Pak Yan—would order the project sealed, declaring it a threat to the island’s cultural and environmental sanctity. This clash—between a bureaucratic “yes” and a political “no”—does not merely reveal a failed investment. It exposes the schizophrenic soul of Bali’s governance, where the left hand of technical procedure builds what the right hand of political will must later demolish.

Act I: The Paper Trail to the Precipice

The narrative, as documented in cold administrative ink, is one of meticulous compliance. In response to a formal request from the Klungkung Regency PUPR Office (No. 005/28.11.2/XI/DPUPRPKP-CK, dated November 28, 2022), a technical team from the Provincial PUPR conducted a site visit on December 16, 2022. The investor submitted a Detailed Engineering Design (DED) and a Hydrological Study, received by the office on January 24, 2023. The next day, the recommendation was issued.

The technical reasoning was precise, almost elegant in its clinical detachment:

- The lift base was planned at 6 meters above sea level, safely above the calculated highest wave point of 5 meters (with a 0.01% occurrence frequency).

- The construction was on private land, not public coastal zone.

- The bay showed no significant abrasion.

From a narrow engineering perspective, the case was closed. The letter, however, contained a glaring and prophetic omission: a cluster of borpile (bore pile) foundations shown in the design, planted directly on the beach sand. The recommendation explicitly stated, “the function of these borpiles is not explained in detail… therefore, this aspect is not part of the technical study.” The structural safety of these critical elements was casually outsourced, with responsibility tossed back to the investor. The bureaucracy had issued a permit for a head, while wilfully ignoring the unstable legs.

Act II: The Governor’s Veto and the Investor’s Ruin

Here lies the devastating paradox. The investor, following the rulebook to the letter, had navigated the labyrinthine permit process. They had obtained the sacred technical recommendation—the golden ticket for any project. They had played by the rules of “Investor Bali.”

Yet, they were blindsided by the rules of “Political Bali.” Governor Koster’s decisive closure was a verdict from a different court, one adjudicating not wave height calculations, but cultural sacrilege, visual pollution, and the existential brand of “Bali-ness.” The project was not rejected for technical failure, but for philosophical incompatibility. The investor’s millions, and their faith in the system, were rendered null by a higher-order decision that the bureaucracy’ own processes had failed to anticipate or filter.

This is the ultimate betrayal of trust. It reveals a system where the technical pathway and the political destination are not connected. An investor can win every bureaucratic battle yet lose the war in a single gubernatorial press conference. The message to the business community is paralyzing: You can comply with every regulation and still be wrong.

Act III: The Real Cliffhanger: Who Governs Bali?

The Kelingking elevator saga is not a story about a misguided project. It is a symptom of a profound governance crisis.

First, it highlights the dangerous divorce between technical approval and holistic vision. A department can approve a project in a silo, assessing only hydrology and soil mechanics, while remaining utterly blind to its catastrophic impact on landscape aesthetics, cultural spirituality, and tourism perception. The PUPR’s letter is a masterpiece of myopia, expertly measuring the tree while missing the forest it would destroy.

Second, it showcases the absence of a unified, pre-emptive ethical gate. Why was there no mechanism—a cross-sectoral committee evaluating cultural and environmental congruence—before the investor spent fortunes on detailed engineering? The current system incentivizes investors to chase paperwork, not wisdom, only to be stopped at the finish line by a political referee.

Third, it poses the fundamental question: What is the “technical” duty of the state in a place like Bali? Is it merely to calculate load-bearing capacity, or is it to fiercely guard the genius loci—the spiritual and visual integrity of a landscape that is both a cultural heirloom and an economic engine? The PUPR’s narrow mandate failed this second, more sacred duty.

Beyond the Rubble of Kelingking

The sealed construction site at Kelingking is more than a halted project. It is a monument to a broken process. For Bali to move forward, it must heal this rift.

- Create a Pre-Clearance Cultural & Environmental Tribunal. No technical application should be entertained before a super-body—incorporating cultural leaders, environmental scientists, tourism experts, and spatial planners—issues a preliminary verdict on a project’s fit with Bali’s fundamental values.

- Mandate Integrated Impact Assessments. Technical studies must be legally required to include chapters on visual impact, cultural significance, and long-term carrying capacity, forcing engineers to dialogue with anthropologists and artists.

- Demand Political Courage at the Start, Not the End. The governor’s ultimate veto was correct, but it came too late. That same principled stand must be embedded at the very beginning of the regulatory framework, saving investors from themselves and protecting Bali from death by a thousand technical permits.

The glass elevator at Kelingking was destined to be a coffin for the view. Instead, it has become a glass coffin for blind bureaucracy itself. We must hope that within it, buried for good, lies the old way of doing things—where a signature on a form could outweigh the soul of a cliff. The future of Bali depends on building a system where technical rigor and spiritual reverence are not opposites, but the twin pillars of every single decision.