PETANG, Badung — On a bright January morning, the sacred precincts of Pura Beji in Kiadan Village are not filled with solemn whispers, but with the joyous cacophony of a battle. The air thrums with gamelan and erupts with laughter as young men and women, clad in white and checkered poleng cloth, face each other.

In their hands are not weapons, but symbolic offerings: men hold pointed tumpeng rice cones, women carry flat, disc-shaped untek rice cakes. This is Siat Untek or Perang Nguntek—a centuries-old Balinese fertility ritual where ceremonial combat pleads with the divine for the earth’s abundance.

This Hindu ceremony, believed to date to the ancient Warmadewa Dynasty, transforms the abstract prayer for agricultural success into a vibrant, physical metaphor. It is a profound enactment of the union of opposites, where the community itself becomes an instrument of blessing.

“The untek, which is flat, symbolizes pradana or the feminine principle. The tumpeng, which is pointed, symbolizes purusa or the masculine principle,” explains I Nyoman Laba, the village head (Bendesa Adat) of Kiadan. “From the meeting of purusa and pradana, it is hoped that it will give birth to goodness.”

The Sacred Arithmetic of a Fertility Ritual

The power of this traditional religious festival lies in its sacred geometry. The ritual’s precision is itself a form of devotion, a coded language of numbers and directions speaking directly to the cosmos. Exactly 777 untek cakes, representing the life force (pengurip) of the entire universe and all its directions, are prepared. They face 555 tumpeng cones.

The yellow untek are stationed in the east, the white tumpeng in the west, creating a perfect, balanced mandala of symbolic meaning upon the temple grounds.

This is not mere pageantry but a meticulously calibrated spiritual technology. “The number of ceremonial items used is not arbitrary,” Laba notes, emphasizing the deep intentionality behind every element of the Siat Untek fertility ritual. Each quantity and color is a deliberate prayer, ensuring the community’s plea for abundance is framed within the universal order.

Water, Laughter, and the Promise of Harvest

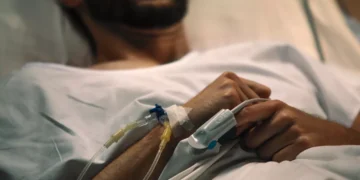

The choice of location is the ritual’s foundational truth. This profound annual temple ritual is held not at the main village temple, but specifically at Pura Taman Beji, a temple dedicated to the source of life itself: water.

“We conduct it here at Pura Beji because, of course, to pray for fertility, we go to the place of water,” Laba states, linking the ritual’s intent directly to the elemental wellspring of all agricultural life. In the Balinese worldview, no prayer for growth can be separated from tirta, holy water.

As the ceremony peaks, the symbolic confrontation erupts into a playful, riotous exchange. Men from the east and women from the west gleefully pelt each other with the rice cakes, their shouts and laughter rising to the heavens alongside the gamelan’s rhythm.

The hoped-for outcome is a direct hit—a symbolic union that fertilizes the very air. “We believe that after Siat Untek is held, our harvests will be successful, or in Balinese, mupu—to gather abundance,” Laba shares.

For the global reader, Siat Untek dismantles any sterile notion of a traditional religious festival. Here, faith is kinetic, communal, and drenched in the palpable joy of laughter.

It is a powerful, living reminder that in Bali, the sacred is woven into the most fundamental human concerns—water, soil, and sustenance. The ‘war’ fought in the highlands of Badung is perhaps the most generative conflict imaginable: a battle where every thrown cake is a seed of hope, and the only victory sought is a future where the earth, and its people, flourish together.