A suicide note from a fourth-grader in East Nusa Tenggara, written in his local dialect, exposes the silent despair borne of poverty and has ignited a national reckoning on child welfare and mental health.

Disclaimer: The following article contains discussion of a distressing incident. If you or someone you know is experiencing emotional distress or thoughts of self-harm, please seek help immediately from a mental health professional or a trusted crisis hotline.

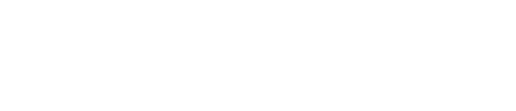

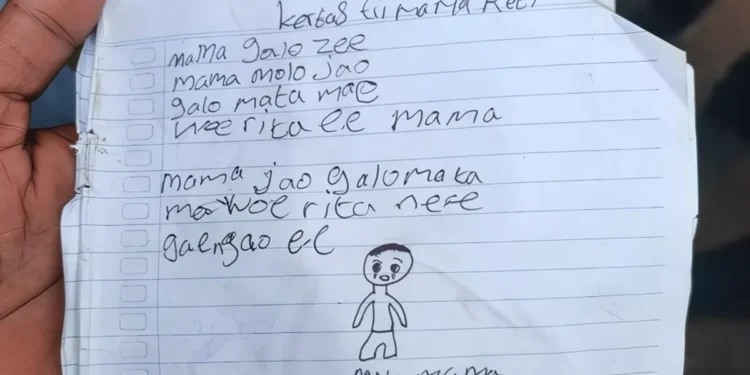

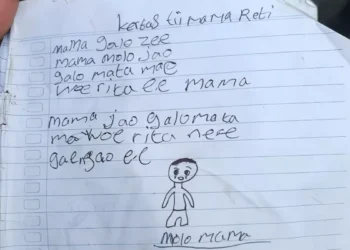

In a remote clove grove on the island of Flores, East Nusa Tenggara, a final, handwritten note was found beside the body of a 10-year-old boy. Penned in the local Bajawa language on a page titled “Kertas Tii Mama Reti” (Letter for Mama Reti), its few lines conveyed a world of unmet need and profound, childish misunderstanding. “Mama Galo Zee (Mama is so stingy),” he wrote. The words that followed were instructions of heartbreaking finality: “Mama baik sudah. Kalau saya meninggal mama jangan menangis… Mama saya meninggal, jangan menangis juga jangan cari saya ee (Mama, it’s okay. If I die, don’t cry… Mama, I’ve died, don’t cry and don’t look for me).” It was signed, simply, “Molo Mama (Goodbye Mama).” Police confirmed the authenticity of this raw, devastating farewell from a fourth-grader known by his initials, YBR.

The catalyst for this unspeakable act, according to village and police officials in Ngada regency, was a denied request the night before. The boy had asked his mother for money to buy a notebook and a pen for school—basic tools of learning and dignity.

His mother, separated from the father a decade ago and the sole provider for five children in a condition described bluntly by the village head as “susah” (difficult), could not fulfill it. YBR, who lived primarily with his grandmother in a simple pondok near the clove tree, returned there. The next morning, he did not go to school.

A Tapestry of Vulnerability

The tragedy is woven from threads of systemic hardship common in Indonesia’s less-developed regions: intergenerational poverty, fractured family structures due to economic strain, and the immense, often invisible, psychological burden these place on children.

YBR’s life between his grandmother’s hut and his mother’s home in a neighboring village reflects a familial dispersal aimed at survival, but one that can leave a child feeling emotionally and materially unanchored.

In this context, the unaffordable notebook and pen were not just stationery; they were symbols of participation, hope, and a normalcy perpetually out of reach.

Reactions from the Apex: A Call for ‘Shared Attention’

The incident has provoked responses from Indonesia’s highest offices, framing it not as a private misfortune but as a public policy failure. Minister of Social Affairs Saifullah Yusuf (Gus Ipul) expressed profound sorrow and stated the tragedy must be “a shared attention.”

He pointed to the critical need for “strengthening data” and “reinforcing assistance” to ensure no family in need slips through the bureaucratic cracks. His comments highlight a persistent challenge: social aid cannot reach those it cannot accurately identify. Meanwhile, the Minister of Education, Abdul Mu’ti, acknowledged he was not fully briefed but pledged an investigation, underscoring the education system’s role in the holistic well-being of students.

Beyond the Headline: The Unseen Crisis of Child Mental Health

This event forces a painful conversation that extends beyond poverty alleviation into the realm of child psychology and mental health. It challenges the perception that despair is the domain of adults, revealing how deeply children can internalize familial stress and material lack.

The boy’s note, misinterpreting his mother’s poverty as personal stinginess, is a tragic testament to a child’s cognitive inability to process systemic hardship, transforming it into a personal rejection with catastrophic consequences.

The loss of YBR is an unbearable metric of societal neglect. The “shared attention” demanded by the Social Minister must now translate into a multi-faceted response: robust psychological support in schools, community-based monitoring for at-risk children, and a social welfare system that is proactive, not reactive.

The note from the clove grove is more than a personal message; it is a stark, national indictment. As Indonesia mourns, the boy’s simple request for a notebook and a pen now echoes as a powerful, tragic plea for a society that safeguards its children’s minds and hearts with the same urgency as it seeks to fill their school bags.

Comments 1